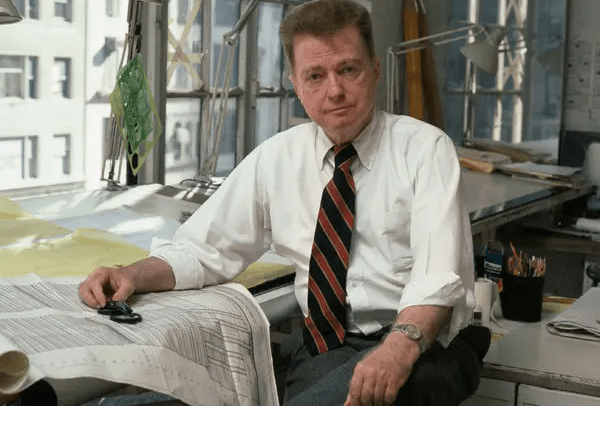

Paul Marvin Rudolph, (born October 23, 1918, in Elkton, Kentucky, died August 8, 1997, in New York, New York). was an American architect and the chair of Yale University’s Department of Architecture for six years. He was known for his use of reinforced concrete and highly complex floor plans. His most famous work is the Yale Art and Architecture Building, a spatially complex Brutalist concrete structure. He is one of the modernist architects considered an early practitioner of the Sarasota School of Architecture. His buildings are notable for creative and unpredictable designs that appeal strongly to the senses.

Rudolph earned his bachelor’s degree in architecture at Auburn University (then known as Alabama Polytechnic Institute) in 1940. He then moved to the Harvard Graduate School of Design to study with Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius. After three years, he left to serve as an officer in the United States Naval Reserve at Brooklyn Navy Yard. During WWII he worked on the design and construction of merchant marine ships. He then resumed studies at Harvard, where his classmates included I.M. Pei and Phillip Johnson. Rudolph was awarded his master’s degree in 1947. Paul Rudolph was gay.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, Rudolph practiced architecture in Sarasota, Florida, first as a designer of private residences for the firm of Twitchell, and Rudolph later worked independently. His early designs used the glass walls and austere geometry of the International Style but attracted attention by their ingenious construction and attractive lines. Rudolph came to believe that a building’s form should develop from and be integrated with its interior uses and structure, and this led him to break up a building’s masses into distinctly articulated units that are interesting from both the inside and the outside. His early orchestrations of different units were regular and rather symmetrical, as in the Mary Cooper Jewett Arts Center for Wellesley College (1955-58).

From 1958 to 1965 Rudolph was chairman of the department of architecture at Yale University. His School of Art and Architecture at Yale University (1958-63), with its complex massing of interlocking forms and its variety of surface textures, is typical of the increased freedom, imagination, and virtuosity of his mature building approach. Considered one of the most defining designs of his career, the ten-story building featured an interior that appeared seamless, flowing, and shot with light. (In 1969 the building was set on fire by student protestors). Rudolph’s Boston Government Service Center (1963) and the Endo Laboratories in Garden City, New York (1962-64), continued a trend toward complex, irregularly silhouetted, and dynamic structures that contain dissimilar but harmoniously combined masses, shapes, and surfaces.

In 1965 Rudolph left Yale to practice in New York City. His practice grew in size and volume and embraced master plans for urban communities as well as designs for campuses and educational buildings, office buildings, and residential projects. Other important works by Rudolph include the IBM Complex at East Fishkill, New York (1962; with Walter Kiddle), and the Burroughs Wellcome Corporate Headquarters, Research Triangle Park, at Durham, North Carolina (1969).

By the late 1960s, Rudolph’s reputation had begun to decline in the United States, as his abstract Modernistic aesthetic began to be eclipsed by the growing popularity of Postmodernism’s revival of historical styles and ornamentation. He continued, however, to find an audience for his designs in Asia. Working from his historic brownstone on Beekman Place in New York City, famous in design circles for the architect’s controversial Modernistic renovation in the 1960s, Rudolph drafted monolithic high-rise projects for such cities as Hong Kong, Singapore, and Jakarta, Indonesia.

During the 1970s the amount of work declined, with most of the projects being private residences and a few large commissions. Rudolph continued to explore themes of scale and modularity with a special emphasis on the experience of scale regarding high-rise buildings.

By the 1980s, Rudolph began to receive several large commissions in Asia. They were located in primarily dense urban settings. His work of this period focused on developing a scale and complexity necessary to relate the building to its surrounding context. Rudolph developed a multilateral expression of scale in his larger commissions to distinguish between the individual’s perception of the scale of the building’s base, the perception from the automobile of the middle of the tower, and the top of the building from far away. As more of Rudolph’s work shifted from the United States to Asia, he explored materials and building forms to relate his Modernist designs to the unique character of the regional architecture of the building’s location.

In the last decade of his life, Rudolph explored the application of traditional building forms with his modernist aesthetic in large-scale projects in Singapore, Hong Kong, and Indonesia. On August 8, 1997, Paul Rudolph passed away in New York City from mesothelioma, cancer that usually results from exposure to asbestos. At the time of his death, he was working on plans for a new town of 250,000 people in Indonesia, and a private residence, chapel, and office complex in Singapore.

Paul Rudolph was a prolific architect whose legacy can be seen all over the world. Living in New York City we are lucky enough to be able to see some of his creations. At Scarano Architect, PLLC, we respect and admire the talent and accomplishments of Paul Rudolph.

Remember, we can help you with your architectural needs. Please check our award-winning designs on our website: www.scaranoarchitect.com and feel free to contact us.

Your satisfaction is our primary goal!