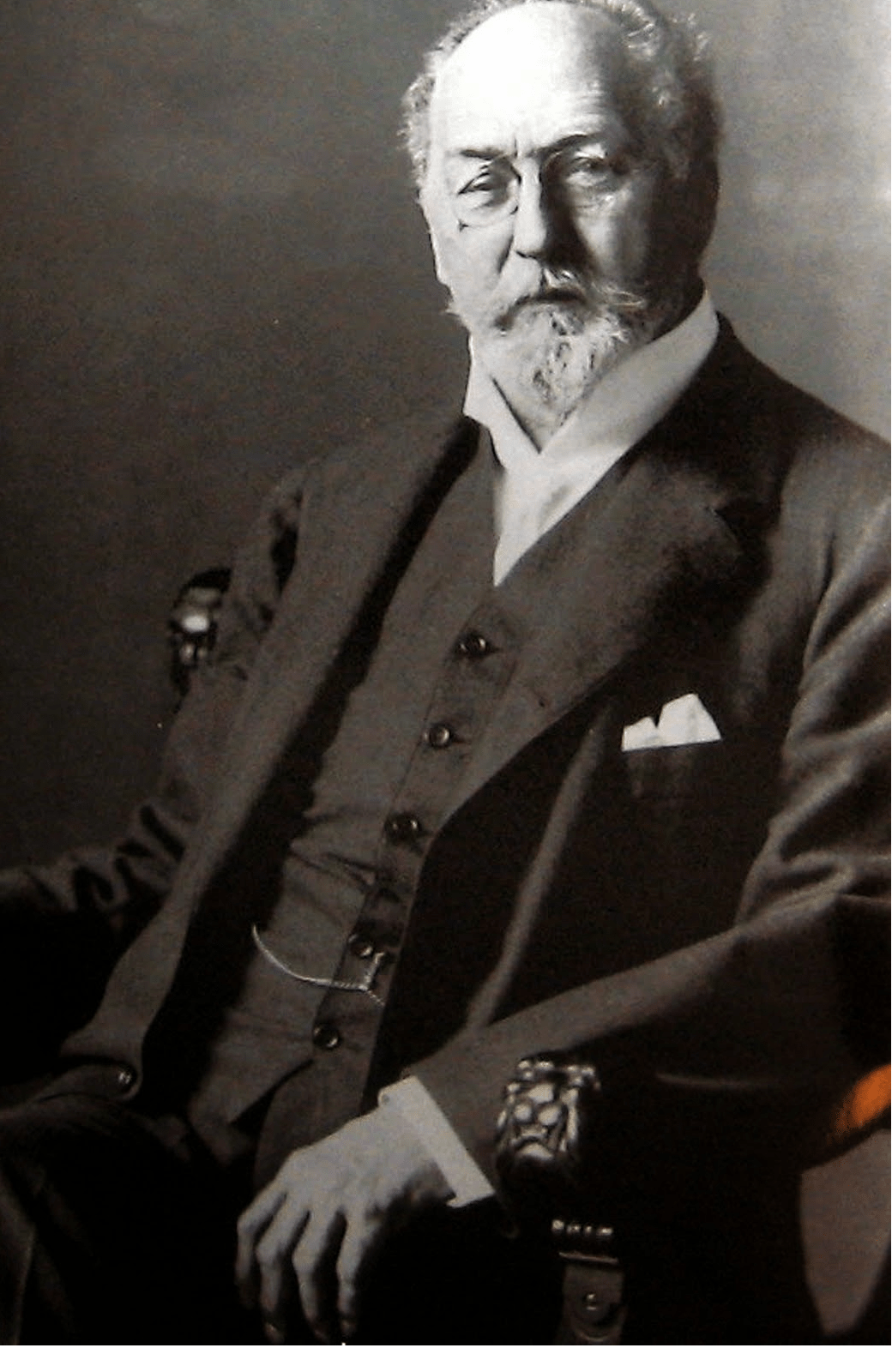

Otto Wagner was an Austrian architect, teacher, and urban planner who was born on July 13, 1841, near Penzing Vienna and died on April 11, 1918, in Vienna. He was a leading member of the Vienna Session movement of architecture, founded in 1897, and the broader Art Nouveau movement. Many of his works are in his native city of Vienna and illustrate the rapid evolution of architecture during the period. His early works were inspired by classical architecture. By the mid-1890s, he had already designed several buildings in what became known as the Vienna Secession style. Beginning in 1898, with his designs of Vienna Metro stations, his style became floral and Art Noveau, with decoration by Koloman Moser. His later works, from 1906 until his death in 1918, had geometric forms and minimal ornament, clearly expressing their function. They are considered predecessors to modern architecture.

Wagner began his architectural studies in 1857 at the age of sixteen at the Vienna Polytechnic Institute. When he finished his studies there, in 1860 he traveled to Berlin and studied at the Royal Academy of Architecture under Carl Ferdinand Busse, a classicist, and student of Karl Friedrich Schinkel was the leader of the German school of neoclassical and neo-Gothic architecture. He returned to Vienna in 1861 and continued his architectural education at the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts, under August Sicard von Sicardsburg and Edouard von der Null, who had designed the neoclassical Vienna State Opera and the architectural monuments along the Vienna Ringstrasse.

In 1862, at the age of 22, he joined the architectural firm of Ludwig von Forster, whose studio had designed much of the new architecture along the Ringstrasse. The first part of his career was devoted to the transformation of that boulevard into a showcase of neo-Gothic, neo-Renaissance, and neoclassical styles. During this period, which lasted until about 180, he described his own style as “a sort of free Renaissance.” He began to develop his own philosophy of architecture, based on the need for buildings to be functional. He continued to develop this idea throughout his career. In 1896, in his book, Modern Architecture, he wrote, “Only that which is practical can be beautiful.”

In the 1880s, Wagner began to construct buildings of which he was both the architect and investor, sharing in the financial benefits. In 1882 he designed a luxury apartment building on Stadiongasse in Vienna. His next major project was the headquarters of the Austrian Landerbank in Vienna. He won the design competition in 1882 and built-in 1883-84.

The following project, in 1886, was the first Villa Wagner, a country house he built for himself on the edge of the Vienna woods. He called it his “Italian Dream,” and it had neoclassical elements inspired by Palladio. It was surrounded by a park carefully designed to complement the architecture. The principal façade had a double stairway ascending to a portico with a colonnade, which was the entrance to the grand salon. The porch was decorated with curving wrought iron, statuary, and a coffered ceiling. At either end of the main villa were pergolas with open colonnades. On either side of the main stairway to the entrance he placed plaques in Latin concisely stating his philosophy on one side, “Without art and love, there is no life;” and on the other side, “Necessity is the sole mistress of art.” In 1895, he modified the house. One of the pergolas was transformed from a winter garden into a billiards room, illuminated by floral stained-glass windows designed by the painter Adolf Bohm. The other pergola was made in his studio, also with colorful decorative windows.

In the 1890’s Wagner became increasingly interested in urban planning. Vienna was growing rapidly; it reached a population of 1,590,000 residents in 1898. In 1890, the city government decided to expand the urban transit system outwards to the new neighborhoods. In April 1984 Wagner was named artistic counselor for the new Stadtbahn and gradually was given responsibility for the design of the bridges, viaducts, and stations, including the elevators, signs, lighting, and decoration. Wagner hired seventy artists and designers for his transit stations, including two young designers who later became very prominent in the birth of modern architecture, Joseph Maria Olbrich and Joseph Hoffman.

Wagner designed stations and other structures which combined utility, simplicity, and elegance. The most notable station he designed was the Karlsplatz station (1894-99). It had two separate pavilions for the two directions and was constructed with a metal frame. It was covered on the exterior with marble plaques and plaster plaques in the interior. The exterior was covered with designs in a sunflower pattern, which continue on the semi-circular façade. The carefully designed gilded decoration gives the building a remarkable combination of functionality and elegance.

In 1894 Wagner became a Professor of Architecture at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, and increasingly expressed the necessity of leaving behind historical forms and romanticism and developing Architectural Realism, where the form was determined by the function of the building. In 1896 he published a textbook entitled Modern Architecture in which he expressed his ideas about the role of the architect; it was based on the text of his 1894 inaugural lecture to the Academy. His style incorporated the use of new materials and new forms to reflect the fact that society itself was changing. In his textbook, he stated that “new human tasks and views called for a change or reconstitution of existing forms.” He wrote in his manifesto on Modern Architecture, “Art and artists have the duty and obligation to represent their period. The application here and there of all the previous styles, as we have seen in the last few decades, cannot be in the future of architecture…. The realism of our time must be present in every newborn work of art.

In 1897, he aligned himself with the Vienna Secession, a movement started by fifty Vienna artists formally known as the Association of Austrian plastic artists. Its founding members included Gustav Klimt, its first President, Joseph Maria Olbrich, Joseph Hoffman, and Koloman Moser. The Secession declared war on the historicism and realism decreed by the Arts academies and called for the abolition of the boundary between the fine arts and the applied and decorative arts of architecture and art. Its goal was proclaimed by Wagner’s student, Olbrich with one of the most famous architectural works of the Secession, Olbrich’s Secession Building (1897-98) with a strong Wagner influence. Its goal was proclaimed by Wagner’s student, Olbrich with one of the most famous architectural works of the secession, Olbrich’s Secession Building (1897-98) with a strong Wagner influence.

Wagner had a strong influence on his pupils at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna and his school included Joseph Hoffman, Joseph Maria Olbrich, Karl Ehn, Jose Plecnik, Max Fabiani, and Rudolph Schindler, who said: “Modern Architecture began with Mackintosh in Scotland, Otto Wagner in Vienna, and Louis Sullivan in Chicago.”

By 1905 Wagner continued to produce new editions of his book Modern Architecture, and three volumes entitled Sketches, Projects, Constructions. He published a series of books on topics including theater architecture, hotel architecture, and a particularly forward-looking work, “The Great City,” published in 1911, devoted to urban planning, explaining how the expansion of large cities should be managed. He participated in the International Congress of Architecture in London in 1906 and traveled to New York for the International Congress of Urban Art in 1910. In the same year, he became the Vice-Rector of the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna. He was named Vice President of the Permanent Commission of the Congress of Fine Arts in Paris in 1912. In 1912 he proposed a very modern municipal museum for Vienna dedicated to the emperor Franz-Joseph. However, the final competition for this building was one of Wagner’s former students, Josef Hoffman.

The project was halted by the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. In 1913, he became an honorary professor at the Academy and retired but continued to tutor students who had enrolled prior to his retirement.

While he proposed many projects, only a few were built. These included a strikingly geometric and modernistic hospital for victims of Lupus Disease in Vienna (1908). His last large-scale project was a building of thirty large apartments on Nestiftgasse and Doblergasse in Vienna. The building had a very modern white plaster façade with the very discreet geometric decoration of blue ceramics (Doblergasse) and pieces of black glass (Neustifgasse). Wagner had his own apartment on the second floor of the Doblergasse building. He designed all the furniture, carpets, and decoration in his apartment, as well as the towels and bathroom fixtures. The ground floor of this building also served as the offices of the Wiener

Werkstatte architectural movement from 1912-1932.

Another of his last projects was the Second Wagner Villa Huttelberg-Strasse in Vienna. It was located near his first villa, which he had sold in 1911. It was smaller than his earlier villa. The building was designed to be extremely simple and functional, with a maximum of light, and a maximum use of new materials, including reinforced concrete, asphalt, glass mosaics, and aluminum. The villa is in the form of a cube, with white plaster walls. The primary decoration elements of the exterior are bands of blue glass tile in geometric patterns. The front door is reached by a monumental stairway to the first floor. The servant’s quarters were downstairs, and the main floor was occupied by a large single room, which served as a salon or dining room. For the furniture, he selected many works designed and manufactured by one of his former students Marcel Kammerer. Wagner intended the house as the main residence of his wife after his death, but she died before him, and he sold the house in September 1916.

Wagner died on April 11, 1918, shortly before the end of the First World War, in his apartment on Doblergasse in Vienna. He led a rich life fueled by artistic expression. He broke with tradition by insisting on function, material, and structure as the basis of architectural design. Wagner’s early work was in the already established Neo-Renaissance style. In 1893 his general plan (never executed) for Vienna won a major competition, and in 1894 he was appointed academy professor. Though much attacked at first, Wagner became widely influential. His lectures were published in 1895 as Moderne Architektur. An English translation appeared in The Brickbuilder in 1901.

Otto Wagner was an architect that left an indelible mark on projects all over Europe. He was an enormous influence on many young architects to come after him. We at Scarano Architect PLLC, enjoy reading about those architects that helped shape the world. We are proud to say we are doing the same. Please visit our website to see our award-winning designs. Feel free to call us if you need help with any of your design or building needs.